“The Ludic Archive: The Work of Playing with Optical Toys,” The Moving Image 16.1 (Spring 2016): 1-16.

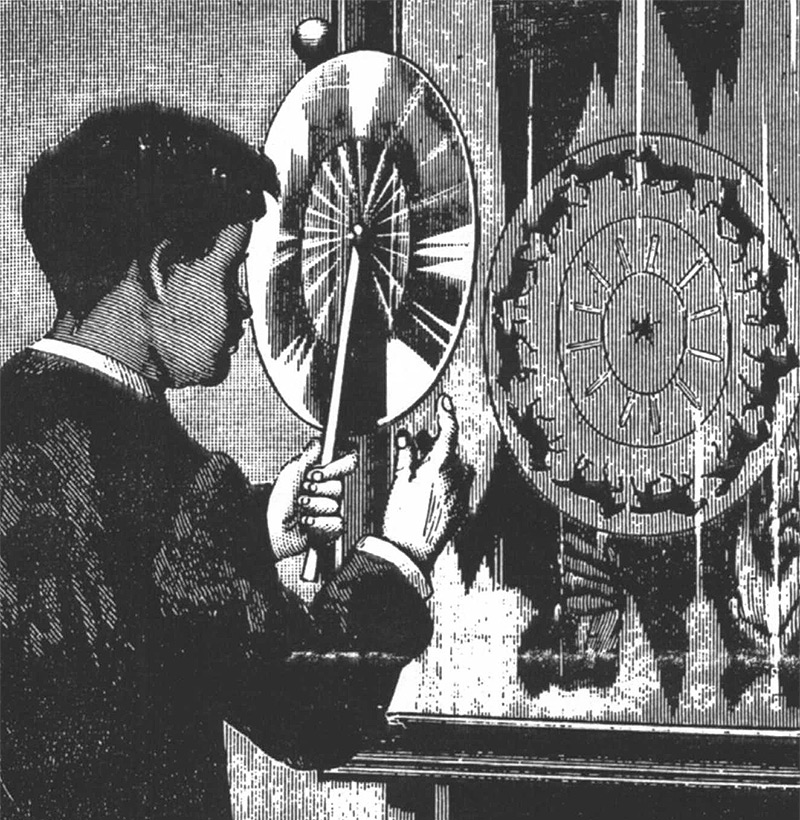

Pre-cinematic optical toys such as the thaumatrope, zoetrope, and phenakistoscope have enjoyed renewed critical attention in recent years as objects implicated within histories of cinema and within visual culture more broadly. Work since Jonathan Crary’s Techniques of the Observer (1990) has focused not only on these toys’ disciplinary attributes, but also on their status as toys, as objects that were played with, manipulated, and animated in use. Although optical toys have been extensively theorized, the unique challenges and opportunities associated with studying optical toys in archival settings have been under-examined. This essay argues for play as a key methodology in the archival study of such pre-cinema apparatus. Eschewing romanticized conceptions of play, I argue that some of play’s central features, such as repetition and improvisation, as well as the dynamic interplay between researcher and archivist/collector are vital in thinking through the broader significance of optical toys within historical and contemporary film and media culture. Encountering these toys in archives requires assembly, experimentation, and tactile manipulation, which the researcher must do while simultaneously negotiating the challenges of working with fragile, fragmented, or incomplete objects. However, these physical encounters, which enable the researcher to inhabit the role of the nineteenth-century user, importantly reveal details such as patterns of wear and design variations. For example, it is often the most worn, vulnerable, or delicate features that signal the most attention lavished upon them by their previous owners. Similarly, the size, complexity, and various classification of these objects (as both “hardware” and “software”) often challenge or exceed the boundaries of institutional access policies: it is frequently necessary to “play with” the rules governing access in order to operate and experience these devices. Play becomes an especially important theoretical lens and methodological approach when considering these toys as objects related to historical childhoods, which represents an important disciplinary vantage point in addition to the contexts of intellectual property or the history of media technology. The essay will draw from examples from my archival work with optical toys in collections at institutions such as the Museo Nazionale del Cinema in Turin, the George Eastman House, the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum at the University of Exeter, the Cotsen Children’s Library at Princeton, the American Antiquarian Society, and the Strong National Museum of Play, as well as several private collections.